Blobs ‘R Us

You may have noticed that home décor has become more, well, squishy in the past few years. If so, you’re not alone. Much has already been written about the invasion of blobby design (also here, here, here, and here). In fact, in April Architectural Digest announced the “Blob sofa” as the It item tastemakers can’t get enough of. While blobs seem like a fun fad, there’s much more at play here. I see them as part of a larger trend happening throughout our culture today: a demand for authenticity and inclusion in all aspects of society.

How does a goopy candle signal societal change? When its very existence is a Promethean act. Designed by Mark Talbot and Youngjin Yoon in 2015, the deflated pastel Goobers (pictured above) evoke a range of emotions from customers, most of whom purchase the candles without ever intending to light them. Goobers are cute, pet-like, and to some, exude confidence in the way they seem to promote body inclusivity. The point is, we read what we want into these small shapeless objects. They reflect us—both our hopes and our insecurities. And they're not alone.

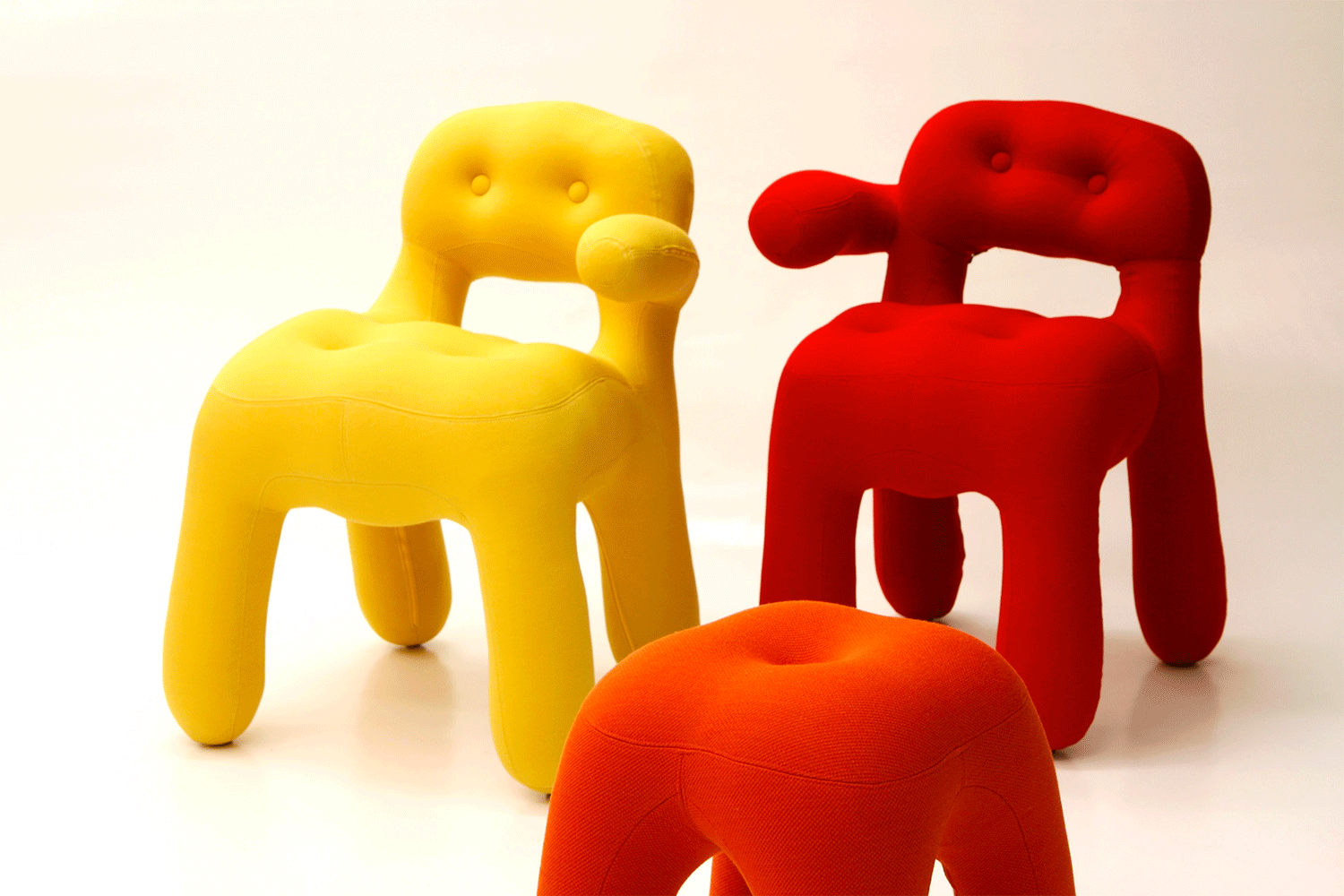

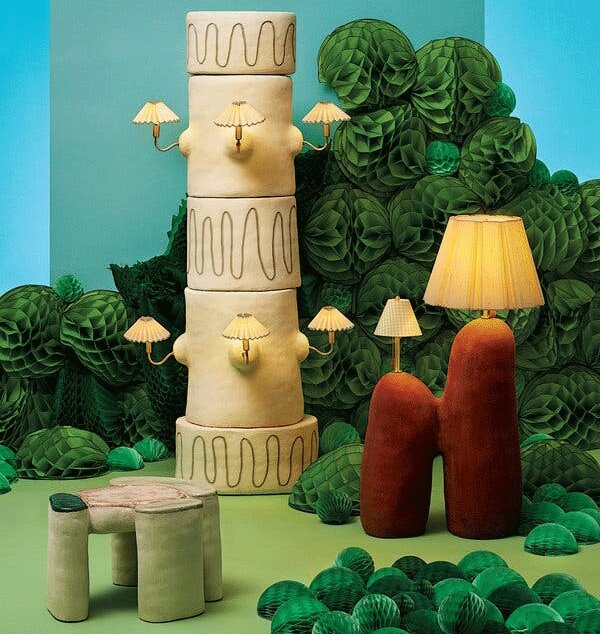

When the Goobers first arrived on the scene they were soon accompanied by other types of neotenic pieces. Blobby chubs started appearing on clothing, in UX design, on restaurant walls, and finally, yes, in our homes. During the same time period we have seen a societal shift toward valuing “real beauty,” a phrase first used by Dove when it launched its 2004 campaign proclaiming “beauty is for everyone” (point of fact, Dove introduced “Real Beauty” bottle shapes in 2017 to “match your body type.”) Valuing authenticity means valuing imperfection. Is it any wonder then that our desire for the voluptuous has started to enter our home décor? From #nomakeup selfies to plus-sizes on the runway, authenticity and aesthetics have become intimately tied.

Dove’s 2017 “body shape” bottles were not popular on social media.

But the rise in neotenic design extends beyond just a consumer desire for inclusivity. It should be no surprise that this lust for lumpiness coincides with an increased interest in late 20th century décor. Postmodernism’s many iterations included much more than the brightly colored blocks and terrazzo patterns of the Memphis Group. Blobism, or blobitecture, became one aspect of the movement in the mid-1990s (though the term “blobitecture” wasn’t used until 2002). Made possible with the advent of CAD software, these amoeba-shaped buildings bubbled across the globe in a steady simmer, conquering preconceived notions of what architecture should be.

Though hard to define, at its core postmodernism was a departure from modernism’s utopian ideals. Rather than simplification and reduction, postmodernism sought complexity and confrontation. It was loud. It was ugly. It was in your face. If modernism was your polite midwestern cousin, postmodernism was your brash uncle from the Bronx.

Alessandro Mendini, Proust, 1978

Am I saying postmodernism was more “authentic” than modernism? Sort of. Modernism may have demanded a truth to materials, but postmodernism spoke to truth to power. It is hard to look at Alessandro Mendini’s Proust armchair (designed 1978) and find much authentic about it. From its faux 17th-century bergère shape to its hand-painted Signac-inspired upholstery, the only thing authentic about it is its intended kitsch. But that’s the whole point. Postmodernism expressed a subversive irony well before it was co-opted by Brooklyn hipsters.

While this trend will continue to morph and evolve, the greater shift toward inclusivity will not go away any time soon. It is a value held strongly by GenZ, whose “adorkable” aesthetic is quietly taking over our social feeds. In five years, blobs will likely be a thing of the past, but GenZ, who will be entering their prime spending years then, will have moved on to a new favorite thing.